The U-M Depression Center and Department of Psychiatry are finding ways to treat veterans, students, and others where they are, changing the lives of people who may not otherwise receive mental health treatment.

Author |

With two swift actions, Bianca Racine's descent shifted into free fall. First, she yelled at her command sergeant major, something a specialist in the Army should never do. Then she was so angry with herself that she punched a tree.

Her hand bloodied and spirit broken, Racine was told by her sergeant to get help immediately. He told her to contact the man who had been attending armory meetings for months, the one Racine never wanted to talk to even though she knew he was there to help soldiers like her. What could a Vietnam veteran have to offer her, a 20-something LGBTQ soldier who had enlisted during the "don't ask, don't tell" era, served in Kosovo, and had learned to take care of problems on her own?

Now she had no choice. Talk to Bob. Fine. But she wasn't going to open up to him, and she was sure that whatever good intentions he had, he wouldn't be able to help her.

When they met, Racine told Bob Short about what she had done. "Did the tree punch back?" he asked. And with that, he broke down the first of many barriers. Racine opened up, and Short helped her find a therapist, get treatment through a Veterans Affairs hospital, switch to another VA hospital when the first one didn't work out, find a job, and get signed up for the GI Bill to pay for her education.

She also learned that she wasn't alone. "Whatever you've been through," Racine says, "somebody else has, too."

Veterans, Students, and Residents of Remote Towns

Bob Short and Bianca Racine met through Buddy-to-Buddy (B2B), a peer-to-peer outreach program that trains veterans to support service members and other veterans. Short was the training coordinator for B2B and was a volunteer at the Augusta Armory in southwestern Michigan when he and Racine began working together.

B2B is part of Military Support Programs and Networks (M-SPAN), a suite of military mental health programs offered by the U-M Depression Center and a variety of partners. The M-SPAN programs also include Peer Advisors for Veteran Education (PAVE), which connects incoming student veterans on college campuses with successful trained peers who are upper-class students at their colleges and universities; Strong Military Families, which supports military families who have young children; HomeFront Strong, a resiliency program for post-9/11 service-member and veteran spouses; and After Her Service, a resiliency program for post-9/11 women veterans. When peers are involved, they are trained by experts from M-SPAN, are given access to an online resource database, and receive weekly support calls.

"Peer support is vital to these veterans, service members, and families," says Michelle Kees, Ph.D., principal investigator for a majority of the military-focused programs within M-SPAN. She also is a clinical psychologist and associate professor in the Department of Psychiatry and a member of the Depression Center. "We are building a community that helps families with a key challenge: isolation. They easily connect with each other because they have a shared narrative about being in the military.

"This is such a strong population — those who have served in the military as well as their families," she adds. "I am constantly in awe of their resilience."

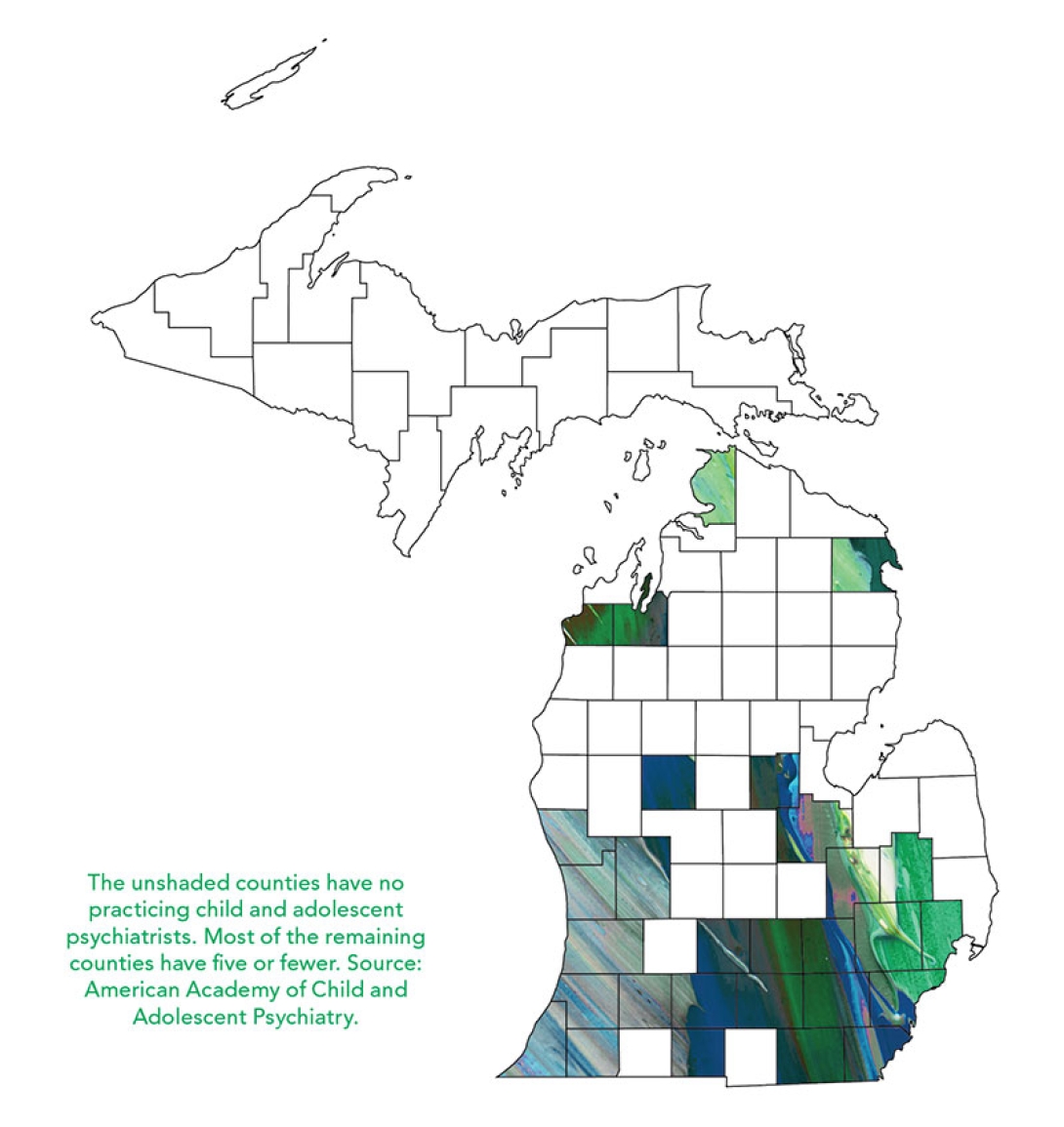

In addition to its outreach to service members, veterans, and family members, the Depression Center offers programs that help high school students around the state and residents of distant regions of Michigan where there isn't access to mental health professionals. Collectively, the programs broaden the reach of the Depression Center and Department of Psychiatry far beyond Ann Arbor's borders. The programs also allow people to find treatment where they are: military bases, schools, and the smallest towns in the most remote areas of the state.

"We have to meet people, culturally and geographically, where they are," says Elizabeth Koschmann, Ph.D., program director and founder of TRAILS (Transforming Research into Action to Improve the Lives of Students), researcher in the U-M Department of Psychiatry, and a member of the Depression Center. "When I think about an upper-middle-class family, and the many resources they have at their fingertips, it's hard enough for them to get mental health care. For average families, cultural barriers on top of limited time, money, transportation, the stigma of entering a clinic building, and poor recognition of mental health as a disease all prevent kids from accessing the mental health care they need."

Another potential barrier is long wait times. One way of bridging that gap is with the Michigan Child Collaborative Care (MC3) and Michigan Depression Outreach & Collaborative Care (M-DOCC) programs, which provide psychiatry support to primary care providers throughout the state who are managing behavioral health problems. Psychiatrists at U-M communicate with physicians by phone and can work directly with patients and their families via telemedicine.

Such a service is vital in a state like Michigan, where a majority of the counties have no child psychiatrists, and where many areas lack adequate mental health care for adults as well, says Sheila Marcus (M.D. 1983, Residency 1989, Fellowship 1991), professor of psychiatry and a member of the Depression Center. Combined with the remoteness of much of the Upper Peninsula and the northern Lower Peninsula, this otherwise could mean that mental health care simply wasn't an option for residents in these areas, says Marcus, the director of MC3 — which won the Michigan Medicine 2017 Dean's Award for Local Community Service.

"We've learned that 'if you build it, they will come' just isn't the reality," says Marcus. "We offer some of the best mental health care in the state at U-M, but so many people simply can't get here.

"We have provided just-in-time phone consultations or resources for more than 5,000 patients, including more than 600 patients last year alone," adds Marcus. "This gives people the ability to have a relatively quick appointment or assessment where they are, where they live."

Help for Students, Efficiently and Effectively

Elizabeth Koschmann had already been in contact with guidance counselors at local schools after some difficult events in 2011 and 2012. So when the guidance counselors at Ann Arbor's Skyline High School realized they were "drowning in student mental health problems," Koschmann recalls, they contacted her. She quickly realized that the problem was vast — and that she wanted to help fix it.

"Every day across the country, students are walking through the doors of schools in every city who are severely impacted by mental illness. The student with depression or anxiety or post-traumatic stress disorder who actually makes it to the office of a qualified mental health professional is unbelievably rare," Koschmann says. "School is often the only source of behavioral health care that students will get. If that care isn't available, students aren't going to get better."

Koschmann's program, TRAILS, began with some schools in and around Ann Arbor in 2013. The goal is to bring evidence-based mental health care approach-es, such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and mindfulness, into the schools. The early response was powerful. Students responded well to their guidance counselors' use of CBT and to group sessions within the schools that helped them realize they were not alone. "Using the CBT program in school, you are part of a group where everyone is going through something and you don't have to feel embarrassed or left out," says a student named Brittany, who participated in the program a couple of years ago. It worked so well that her classmates chose her as one of the school's graduation speakers — and, despite a history of severe anxiety, she felt confident enough to carry out the speech.

Such success stories suggested to Koschmann that the program could — and should — be incorporated at more schools around the state. Her team has piloted TRAILS at 24 schools in 10 Michigan counties, and a recent grant from the National Institute of Mental Health will help spread it to every county in the state. A new Flinn Foundation grant will put TRAILS in every middle and high school in the Washtenaw Intermediate School District.

Recent trainings have taught community mental health providers how to partner with school counselors and social workers to use CBT with students. One training during the summer took TRAILS to the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, where mental health resources are scarce; as of August 2017, there were no child psychiatrists in the entire 16,000-square-mile peninsula.

"If it were up to me, every kid in every school in America would be learning effective coping strategies," Koschmann says, adding that mindfulness and relaxation are taught in conjunction with CBT to help students learn how to cope with their difficulties.

"In many ways, this is not so much therapy as it is providing them with basic skills."

Bringing CBT and other tools to his students has been vital to Brian Williams, a counselor at Ann Arbor's Community High School and one of the initial participants in TRAILS. "Before TRAILS, I always felt I could connect with students, but I never felt I was helping them effectively and efficiently," Williams says. With the CBT training he received from U-M, he says, "I can still form those relationships with students, but I'm able to help them more quickly."

"The talk therapy we were doing in the past wasn't working," says Amy McLoughlin, a counselor at Skyline High. "We needed CBT and we needed an expert who could come in and do that. [When working with TRAILS], you feel like a professional who is being supported."

One of the students who was helped by the TRAILS program was a young man named Marlon. He worked with his guidance counselor at an Ann Arbor school using CBT and participated in sessions with his peers. "I used to be really down on myself a lot. I was really angry a lot. It really does help you a lot with things you may be dealing with.

"Just being aware that there is a way out is good enough."

Telemedicine Fills a Gap

Grayling, Michigan, is the home of endangered-warbler tours, black morel hunting, and a spectacular fall color tour. It is not the home, however, of a single child psychiatrist.

Pediatrician Valda Byrd, M.D., moved to the area in 2011 after working as a private practitioner in Troy, Michigan. She knew that, in the rural northern Michigan town, she would see patients for more mental health issues than she had in the Detroit suburb because the northern Michigan residents would see their primary care physician for mental health needs. How would she help them? Her options seemed few, since in remote areas, specialty care resources can be scarce.

But Byrd was in luck; shortly after she arrived in Grayling, U-M began its MC3 telemedicine program to help physicians in situations just like hers. "It was a huge relief for me," says Byrd, who practices at Munson Healthcare Grayling Hospital. She has participated in MC3 ever since then. "We're able to call and get help within 24 hours. Because of their guidance, I've become a lot more comfortable managing issues that I would have referred out when I was in Troy."

Byrd recalls seeing one patient, a boy of about 8 years old, who couldn't stop running around her office with his brother. Years before, his inability to remain still led his daycare providers to tape him to the floor. When Byrd saw him, he was unable to go to school because of his behavior. He was overweight and over-medicated. Byrd worked with MC3 providers to adjust the boy's medications through the years and to engage non-drug treatments; today, he is 13 years old and attending public school.

She has worked with MC3 on the treatment of dozens of other patients as well, and she knows what questions to ask in anticipation of the consultation with MC3: Did the child have fetal alcohol syndrome? Is there a history of head injuries? Does the child behave the same at home as at school? And so on. "They've helped me to become a better practitioner," Byrd says.

Marcus, the director of MC3 and clinical director of the Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Section of the Department of Psychiatry, says the program has grown rapidly, with 1,500 primary care physicians in Michigan enrolled. Many are in rural or underserved urban counties. They connect with behavioral health consultants in their geographic area, who then can connect them with psychiatrists from Michigan Medicine if they feel it is necessary. Most situations result in a phone consultation, though video consultations also are offered.

"We have a provider satisfaction rate of 95 percent, so I know that we are providing a much-needed service and doing it well," Marcus says. "Despite frequent visits to primary care, most youths with mental health conditions do not receive care for these conditions. We are changing that, patient by patient, phone call by phone call."

Postscript

For Bianca Racine, the veteran from earlier in this story, the Depression Center's outreach programs have been not only lifesaving but also life-affirming. Once she found her footing with buddy Bob Short's help, her entire life changed. She now works at a drug-abuse treatment facility and is a student at Macomb Community College. Her major, impacted heavily by her experience with B2B, is social work.

And she is a volunteer with B2B, helping other veterans and service members through struggles ranging from PTSD to joblessness and homelessness. Her skillset grows almost daily, as she drives around several counties in southeastern Michigan, attending meetings and working with people one-on-one. She is still in touch with Short, as well as her contacts at U-M.

"It has allowed me to find purpose again. I can serve those who have served, and I am supported by an unbelievable group of professionals all around Michigan," Racine says. "I trust the people who have my back."