Editor's note: Joel Howell, M.D., Ph.D., the Victor Vaughan Professor of the History of Medicine, holds appointments in the Medical School, the School of Public Health and the College of Literature, Science and the Arts. To coincide with the University of Michigan's bicentennial in 2017, Howell is working on a history of the Medical School. In this essay, he considers Michigan's place in medical history.

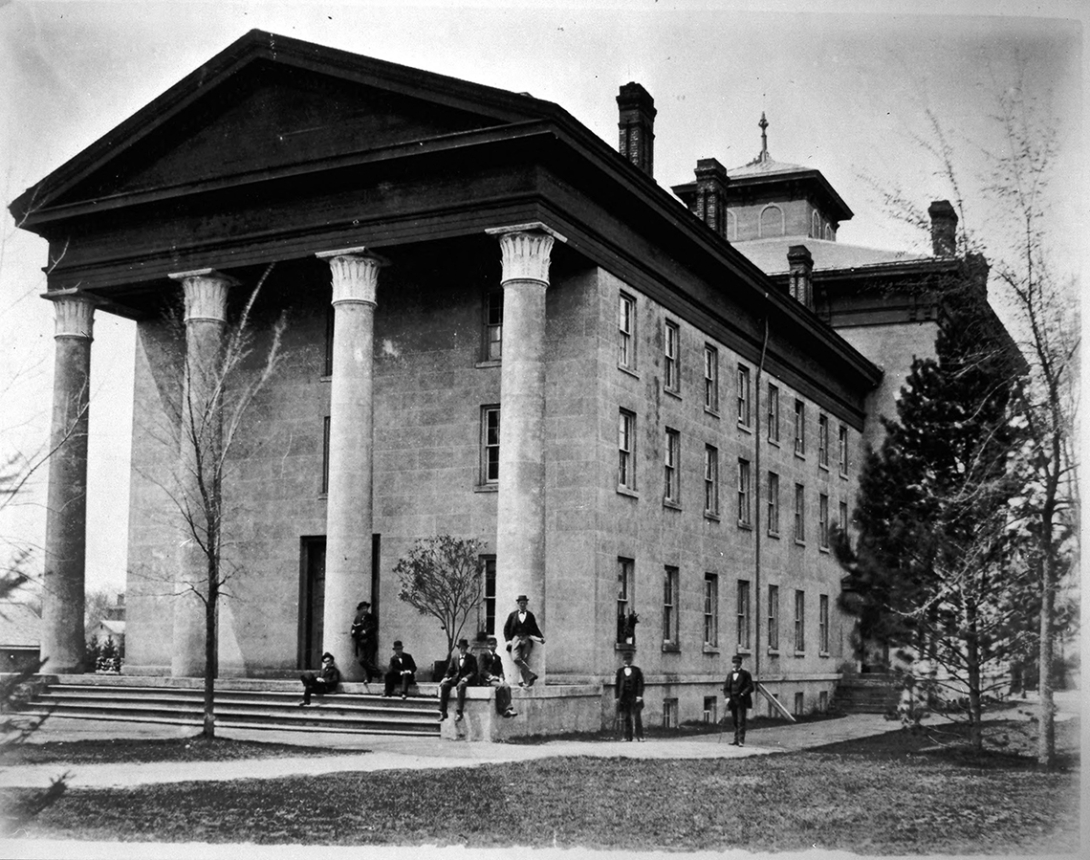

U-M Medical School circa 1890.

Almost 200 years ago, in 1817, the precursor to the University of Michigan was founded in Detroit as the Catholepistemiad, or University of Michigania. Twenty years later it moved to Ann Arbor and became the University of Michigan. Seven students graduated from that first class. The U-M's first professional school, the Medical School, opened its doors in 1850.

Unlike most major medical schools, the Medical School has remained in a small town, but it has had a global impact. Since 1850 the Medical School has grown, leading a broad-based transformation in the ways that medical care is conceptualized and disseminated to people all over the state, the country and the world. It has trained almost 20,000 students and residents. It has been home to thousands of faculty members who have studied topics ranging from the smallest molecules to the health of populations. Over the years Medical School leaders have made key choices that have shaped the institution.

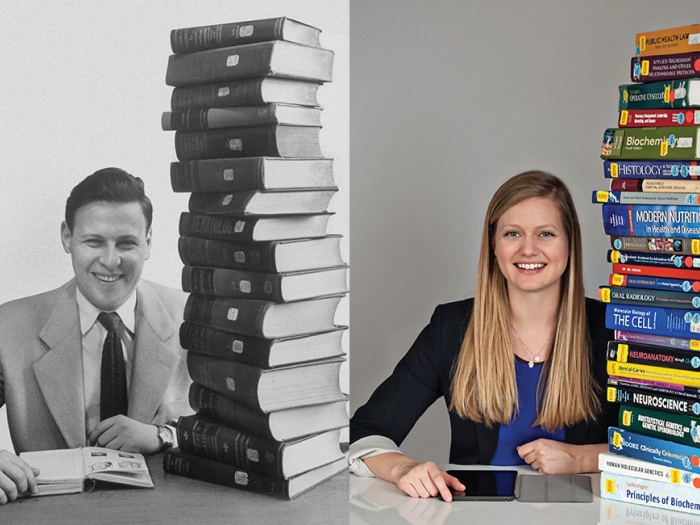

Today, the Medical School is continuing to pave the way for innovative learning and curriculum changes.

One of the early choices was who to admit. In making those choices the Medical School became a leader in admitting a diverse student body. During much of the 19th century, women were perceived as being "ill-suited" to practice medicine, a sentiment shared by not a few members of the Medical School faculty. In 1870 the U-M Board of Regents voted to allow admission of any state resident, making Michigan the first major medical school to admit women. The decision attracted national attention — not all of it positive. Despite some faculty opposition, the first women admitted to the Medical School did quite well. These first women at the Medical School successfully completed their medical degrees, challenging perceptions of gender and status quo. Today, the gender makeup of most medical schools is roughly the same as the makeup of the general population.

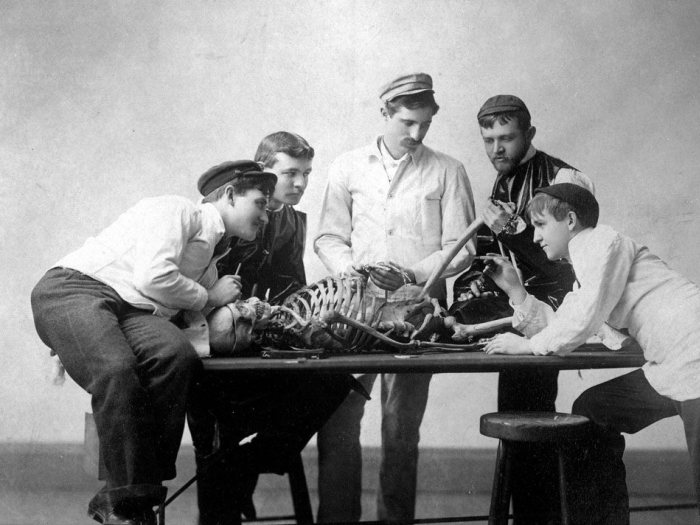

Another key decision involved the essence of the school: how to teach medicine. During the first part of the 19th century, medical education was taught exclusively in classrooms — students sat and professors lectured. There was no clinical instruction or hands-on learning experience, in part because hospitals and clinics were privately owned. But to teach clinical skills, Medical School leaders argued that they needed to operate their own hospital. In 1869, their goal was realized, and U-M became the first university in the United States to own and operate its own hospital. Many other medical schools have since followed Michigan's lead.

Starting a few years later, the Medical School's curriculum was transformed, going from two ungraded years and minimal entrance requirements to four intense years and an expectation of serious college-level preparatory work. A top-tier library was established to keep up with the rapidly expanding scientific literature. Medical school education became based on science, and the educational process became one of learning by doing. Michigan was one of a handful of medical schools that led this transformation. Today, the Medical School is continuing to pave the way for innovative learning and curriculum changes.

Knowledge has long been created at the Medical School. The genetic etiology of sickle cell anemia was established here in the first department of human genetics in the United States. Scholars here did key work on the epidemiology of cardiovascular disease. The current version of the electrocardiogram incorporates 12 leads — nine of which were developed based on work done at the Medical School. For much of the 20th century, endoscopy — the visualization of the inside of the gastrointestinal tract — was accomplished using rigid, uncomfortable and dangerous tubes. But now a safer and much more tolerable flexible endoscope, developed at the Medical School, is in use. These innovations, along with many others, are used daily for the benefit of patients all over the world.

Why is this history important? For one, history is a reminder that knowledge changes. Institutions change. Practice changes. Especially for those learners who pass through the doors of U-M, this is an important lesson. It reminds them that many of the facts taught by their eminent professors will change, sometimes within only a few years. The same lesson is important for the general public: Medicine is not static.

For another, the history of the Medical School can be a source of pride. It can remind us of what has been accomplished in the past, connecting us to a larger community.

Finally, history is perhaps most important because it is liberating. Those who came before at the Medical School made choices — choices about who to teach, what to teach and how to teach. They made choices about how to care for those in need. They made choices about what institutions to continue and what institutions to change. We, too, make choices. Realizing that we are not forced to follow the paths of those who have come before us can free us to look critically at the present as we set out to shape the future.