Until just a few years ago, you could find healing stones at the U-M Medical School. They promised to treat everything from back pain to fertility problems. A doctor would simply touch a stone to the afflicted area to try to offer relief. Sometimes, a patient would hold one and incant the magical spell carved onto the back of the stone. The doctors and patients are long dead now — not because of faulty healing stones, but because they lived centuries ago.

Part of the U-M History of Medicine Collection, some 60 carved stones, many of which are medical amulets, were given to the Medical School by world-renowned surgeon Frederick A. Coller, M.D., former chair of the Department of Surgery. They were originally collected by Campbell Bonner, a U-M classics professor who was the author of the landmark book Studies in Magical Amulets (1950). After a half century at the Taubman Health Sciences Library, the collection was recently moved to the U-M Special Collections Research Center.

Abracadabra

The amulets in the collection gave succor to ancient denizens of the Roman Empire from approximately the first to the fifth centuries. Several stones used for childbirth depict various gods, some Egyptian and some Roman, turning a key on an upside-down pot (a uterine symbol). This image is usually surrounded by an ouroboros, a snake swallowing its tail. Some show a reaper, back hunched, cutting stalks of grain; on the reverse side is a spell for back pain.

Some of the spells are quite long, such as αχτιωψιΕρεσΧιΥαλvεβουτοσουαληΘ. Don't know what that means? You're not alone. Even a scholar of ancient Greek would only be able to offer a transliteration, because it's roughly equivalent to "abracadabra." Others are straightforward to the point of being banal, such as the one that translates to "for the hips."

Modern Crystals

Because rational medicine has evolved exponentially since these medical amulets were in widespread use, it's easy to imagine that ancient people used them because they just didn't know any better. However, healing objects abound in the 21st century as well, despite a lack of scientifically provable efficacy. People may be drawn to them because of the documented power of placebos and prayer, or they may simply feel like it can't hurt to try.

If you type "healing stones" into Amazon, you get hundreds of results. Some are spiritual or religious, like chakra stones and crystals meant to be used in meditative practices. Others are niche, such as the two-pack of "Gem Water Straws" that will allow you to "Turn Every Sip Into a Crystal Elixir." All of them make health and wellness claims. Jade face rollers promise anti-aging benefits, and a "Healing Stainless Steel Necklace" purports to improve sleep, blood circulation, metabolism, arthritis pain, and more. The latter comes in gold, rose gold, and silver, in case you are in the market for a healing necklace.

"Doctors"

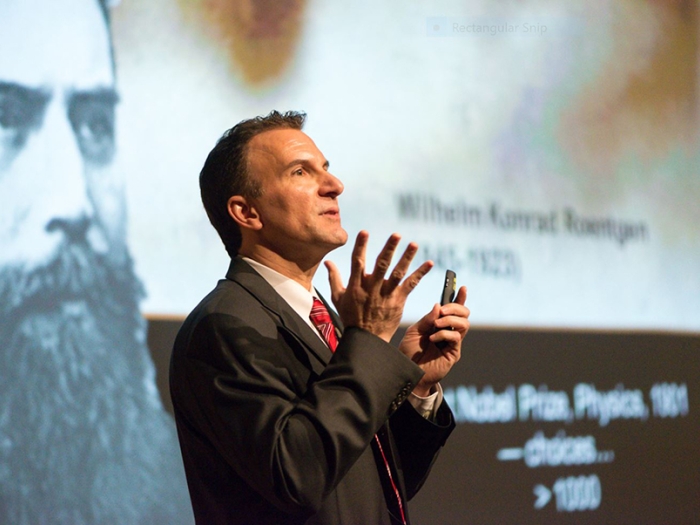

These and hundreds of other items mimic the ancient medical amulets in many ways. Ancient amulets were produced in huge numbers, and ancient believers thought the material of the stone held healing properties, in much the same way modern crystals are purported to have healing benefits. "We have evidence that doctors were using amulets to touch particular parts of the body for healing," says Pablo Alvarez, Ph.D., curator of the U-M Special Collections Research Center. "Of course, when I say doctor, these were doctors in quotation marks." Though there was a rational school of learned doctors, such as Galen, there were also many village "doctors," who may have had some knowledge of healing techniques, but certainly no formal medical training.

Unlike today, the use of amulets in antiquity was much more widespread, and they were used by both doctors and "doctors." They were also used by people in everyday life, as part of their religious rituals. "In ancient religion, people really established a connection with a deity. They did sacrifices, had an altar, and prayed," says Alvarez. "The idea is, 'Now I've done all this, I'm going to get something in exchange. I have a fever, please do something.'" He speculates that modern believers may turn to healing stones when traditional medicine has failed. "If I feel really hopeless and nothing really works, what is left? You have all this paraphernalia, in a way. [They are like] alternative resources."

Several years ago, the U-M Kelsey Museum of Archaeology created an exhibit, in partnership with the Special Collections Research Center, on The Art and Science of Healing: From Antiquity to the Renaissance. You can now view the exhibit online.